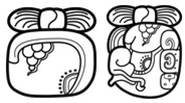

MHD.ZCCa,1&2&3 0186bv 0186hc

SIHOOM

AT-E1168-lecture6.t0:45:33

IHK’:SIHOOM

AT-E1168-lecture6.t0:45:33

YAX:SIHOOM

AT-E1168-lecture6.t0:45:33

SAK:SIHOOM

AT-E1168-lecture6.t0:45:33

CHAK:SIHOOM

· This glyph is for all intents and purposes identical to the full variant of hi – in essence, a KAWAK with a “knot” on top.

o Unlike hi, it can – with enough context – lose the “knot” at the top (hi, if it loses anything, tends to lose the KAWAK, in its reduced form).

o This disambiguating context is very often present, because of the common use of SIHOOM in the four HAAB-month names. Seeing a KAWAK in a position where a HAAB-month is expected (especially when preceded by a coefficient and one of the four colours), will immediately cue for SIHOOM rather than TUUN or ku. That’s why the “knot” is often not needed.

o Unlike TUUN or ku, SIHOOM can have an end phonetic complement of ma, for the -oom. This can be either the 3-dot or the bowtie/butterfly variant of ma.

o This means that all of the following combinations can and do occur, when writing a HAAB-month name:

§ <coefficient>-<colour>-KAWAK.

§ <coefficient>-<colour>-hi-KAWAK.

§ <coefficient>-<colour>-hi-KAWAK-ma.

§ <coefficient>-<colour>-KAWAK-ma.

The ma is usually at the bottom and can be either the 3-dot or the bowtie/butterfly variant. However it can also be at the top (replacing the “knot”), in which case it’s only the bowtie/butterfly variant.

· AT-E1168-lecture6.t0:45:33-47:40: In the calendar you’re going to see a little bit later there are the four so-called SIHOOM months: the Black Sihoom, the Green-Blue Sihoom, the White Sihoom, and the Red Sihoom. We know now from a couple of examples – even though we don’t understand the meaning of the word Sihoom (we don’t have a good translation of the term) – we know it’s a kind of Rain God, or perhaps even a second name for the Rain God. [That’s] because we have names of rulers where Sihoom does catastrophic shaking, like thunder. So a creature who does that has to be a Rain God of some sort. The fact that there are four immediately brings forward the notion of cardinal directions, but only three of these colours are directional. The Yax colour is the centre of the world, or first. So you have one Sihoom who doesn’t come from anywhere – he’s already in the centre, or is already in the centre, or is the first Sihoom. And then three other Sihooms. So if you plot in terms of the significance of colours in the Maya worldview, there is a Black Sihoom who comes from the West, there’s a White Sihoom who comes from the North, and there’s a Red Sihoom [who comes from the East] – nobody comes from the South. Of course, in that part of the world… if you’re in the lowlands, [then] your weather is really not determined by the Pacific: there’s is a huge mountain range of Guatemalan highlands. So for folks in the lowlands, when they think about rain – remember, these are Rain Gods, who give their name to months – so they can[’t?] presumably bring the rain from East, West, and North (South is not important). So when you think about wind perhaps, for the Maya, there were three directions from which the wind would come. They would never come from the South; because in the South they have the mountains – they block everything. So when people look for rains, they look East, they look West, they look North, they never look South.