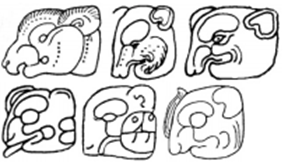

K&L.p13.#1 TOK.p31.r2.c1 BMM9.p17.r4.c4

CHIK /chi’k CHIIK CHIK

SJ.p271.1

= SJ.p249.c1.r8

CHIK

· No glyphs given in K&H.

· This is the animal represented in the month name chikin ç CHIK:ni, translated into English as Xul (that being the Yucatec name for that month).

· Do not confuse this with the phonetically similar chij = “deer”.

· Do not confuse chik with tz’utz’ih / tz’uutz’ which also means “coati”. They both are a mammal head, but tz’utz’ih / tz’uutz’ has a trilobate ear while chik has a regular “mammal ear”.

· Another word for “coati” is tz’utz’ih / tz’uutz’.

· Both K&L.p13.#2 and 25EMC.pdfp32.#3 equate a coati with an agouti and translate CHIK as being either one.

o Agoutis and coatis are very different. The agouti looks like a small capybara. Both agoutis and capybaras are rodents; agoutis are diurnal, while capybaras are diurnal and nocturnal. Agoutis and capybaras, as rodents, have round and plump (like rats), and have roundish snouts, while coatis are raccoon-like and are sleeker and more streamlined, and have longish snouts.

o EB1 lists only coati (chik or tzutzih) and makes no reference to agouti.

o I propose removing all references to agouti, as the logogram shows a longish snout. It seems that agoutis and capybaras are not referred to in Classic Maya, and this is just a terminological confusion in the modern academic works.

· The darkness elements on some of these glyphs is unexpected, as coatis are not nocturnal.

· Memo (Guillermo) Kantun: the SJ example is ji not CHIK.

· Reminder: with a ni underneath, CHIK (perhaps acting as a rebus) gives CHIK:ni è Chikin, the 6th month name in the Haab calendar, with the Yucatec name Xul.

· The reading TZ’IK? comes from MHD and the reading TZ’IKIN comes from Bonn (without a question mark).

![]()

![]()

Boot-BSCTPR.p12.AppE Boot-BSCTPR.p13.AppF

PAL TC R5-S5 PAL Temple XVII Panel B6

bu.<tz’a:ja> SAK.<chi:ku> <bu:tz’a:ja> SAK:<chi[ku]>

· K&H.p64.tabXVII.#8: chi-ku, but no glyphs.

· The chi’ik reading probably comes from the disharmonic spellings shown in PAL TC R5-S5 and PAL Temple XVII Panel B6.

· Boot-BSCTPR.p3-4: Some epigraphers even have translated the nominal phrase b’utz’aj sak chi’ik as “Smoking White Coati” (Schele and Mathews 1993: 137, as butz’ih sak chik). The verb root b’utz’- means “to smoke/humear” (CHOL, CHON, ITZA, LACA, YUC) and sak is the pan-Mayan word for “white/blanco” (cf. Dienhart 1989). // A different translation, however, of this nominal phrase is possible. In colonial Yucatec Maya, the entry çac chic (sak chik) can be found which means “calandria desta tierra, es algo blan[quizca]” (Ciudad Real 1984: folio 93r) and “calandria de esta tierra” or “lark of this country” (Maya Than 1972: folio 32v; Maya Than 1993: 163 [folio 32v]). That sak chik indeed refers to a bird name in Classic Maya may be strengthened by a rare entry in Ch’orti’, namely chi’k “bird [generic, seldom used]” (Wisdom 1950: 704). As its Yucatec Maya name indicates, and the Ciudad Real entry explains, this bird species is slightly white colored (sak “white”; compare to present-day Yucatec Maya sak huuh “white iguana”, sak kay “silverfish”, and sak xíiw “white herb”, cf. Bricker et. al. 1998: 239-240). In later research this bird has been identified as the “zenzontle” or “sisonte de Yucatán”, its Latin name being Mimus gilvus gracilis, Cabot (Barrera Vásquez et. al. 1980: 711; Pearse 1945: 247, in his study referred to as chiko). // In the Western Ch’olan language of Tumbalá they refer to the “calandria” as tojt (Aulie and Aulie 1978: 113), while toht identifies different kinds of robins in Tzeltal (Hunn 1977: xxv, 179-181). Tojolab’al provides choyej for “zentzontle” (Lenkersdorf 1979: 103). As the Western Ch’olan and Chiapanec languages do not contain an item chi’ik for “coati, tejón, pizote”, the Colonial Yucatec entry sak chik “calandria de esta tierra”, supported by the Ch’orti entry chi’k “bird”, may be a valid linguistic item in the interpretation of the Classic Maya name of the third Palenque ruler. I propose to translate the nominal phrase B’utz’aj Sak Chi’ik as “Smoking Lark” or, in Spanish, as “Calandria Humeante”.

· Do not confuse this with the phonetically similar:

o chih = “pulque”

o chij = “deer”

With the loss of the -h vs. -j distinction, chih and chij merged in the late Classic, but this didn’t affect the contrast with chik = “coati”.